- See Seattle Post Intelligencer article: "Seattle Center limits on street performers OK'd -But critics call the appeals court ruling a blow to free speech." By PAUL SHUKOVSKY http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/local/346757_magicmike10.html

- To see this case click at Federal Court web site: http://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2009/06/24/05-35752.pdf

- To see copy of official PDF from this web site click HERE

- Berger v. City of Seattle, 569 F.3d 1029 (2009) Google Scholar link https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=12021124308690069166&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr

- American Law Daily had nice article about lawyers: http://amlawdaily.typepad.com/amlawdaily/2009/06/davis-wright-helps-magic-street-performer-in-first-amendment-case.html

- Article in Seattle Times: Appeals court punctures Seattle's attempt to regulate balloon man -- The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals put a pin in Seattle's efforts to regulate balloon artist "Magic Mike" Berger and other street performers at the Seattle Center, reversing an earlier decision to find that the center's rules violate free speech. By Mike Carter

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2009379403_webbusker24.html

- - Court Injunction: vbbc.files.wordpress.com/2010/10/venice-dowd-injunction.doc

- - http://articles.latimes.com/2010/oct/27/local/la-me-venice-vendors-20101027

- Preliminary Injunction written Memorandum and Order issued July 30, 2013, by United States District Judge Catherine D. Perry HERE

[T]he Court finds that Katra made his measurements in February at the same place and time of day as the October 9, 1999 incident in issue; that 56 decibels was the maximum noise level at which a person could speak and still be in compliance with the ordinance 50 percent of the time; that this decibel level is lower than that generated by the clicking of high-heeled boots, conversations between two or three people, a shop door opening and closing, a small child playing on a playground and a cellular telephone; that most normal human activity would be clearly audible at a distance of 25 feet; and that a spirited conversation between two people would be clearly audible at a distance of 25 feet. The Court further finds that there is no evidence regarding how many people were in "close proximity" (six to eight feet) of plaintiff while he was preaching; that Katra did not measure the decibel level of plaintiff's preaching; that the duration of a loud sound is an important factor in whether it is annoying or alarming; and that factors such as annoyance and alarm cannot be scientifically measured.

Quite simply, a noise regulation that prohibits "most normal human activity," including a spirited conversation by only two people, is not narrowly tailored to serve the City's interest in maintaining a reasonable level of sound, at least in a public forum like the Commons.

DEEGAN v. CITY OF ITHACA, 444 F.3d 135 (2006). http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F3/444/135/546275/ or https://law.resource.org/pub/us/case/reporter/F3/444/444.F3d.135.html

Court case which discusses and gives full First Amendment protection to amplified music. Casey v. City of Newport 308 F.3d 106. 110 (1st. Cir. 2002) Google Scholar Text, Law Resource Text

. amplifiers are also used to create new "messages" that cannot be conveyed without amplification equipment. Amplification enables performers to boost the relative volume of quiet instruments, such as the bass and the lower registers of the human voice, [*29] and to adjust the tonal qualities of voices and instruments without necessarily increasing the overall volume of the performance.Much modern music simply cannot be performed without the use of amplifiers. Thus the ban on amplification has a direct and immediate effect on the expression at issue. The record therefore does not support the district court's conclusion that appellants "could still convey their . . . messages" without amplification. Without amplification, some of the messages are not conveyed at all.

CONCUR: McAULIFFE, District Judge (concurring)

In the world of modern music, "amplified" is not synonymous with "made louder." Electronic musical instruments can only produce sound through a process of electronic amplification, but those instruments are not inherently louder than acoustic or unamplified instruments. A modern synthesizer, for example, can make sound only by means of electronic amplification, yet that amplified instrument easily and faithfully mimics the sounds produced by a wide range of acoustic instruments such as pianos, harps, flutes, acoustic guitars, violins, drums, etc. Moreover, the synthesizer can reproduce those musical sounds as softly and quietly as desired. Yet, the synthesizer falls within the City's ban. An electronically amplified Aeolian Harp can produce the same "soft floating witchery of sound" as nature's own, but the volume is more easily controlled on the amplified version.

- District Court Injunction opinion: vbbc.files.wordpress.com/2010/10/venice-dowd-injunction.doc

- Los Angels Times article: http://articles.latimes.com/2010/oct/27/local/la-me-venice-vendors-20101027

"Other courts have struck down amplified sound restrictions less sweeping than the total ban on amplified sound on the Venice Boardwalk. See, e.g., Deegan v. City of Ithaca, 444 F.3d 135 (2d Cir. 2006) (holding noise regulation as applied to prohibit any sound that could be heard 25 feet from its source in downtown pedestrian mall was not narrowly tailored); Doe, 968 F.2d at 89 (holding regulation prohibiting operating an audio device in a manner exceeding 60 decibels at 50 feet was not narrowly tailored as applied to Lafayette Park because "[b]y no reasonable measure does Lafayette Park display the characteristics of a setting in which the government may lay claim to a legitimate interest in maintaining tranquility"); Beckerman v. City of Tupelo, Miss., 664 F.2d 502, 516 (5th Cir. 1981) (holding ban on amplified sound in residential zones overbroad because "the ordinance extends its total and non-discretionary prohibition to areas which have not been shown to be incompatible with sound equipment"); Reeves v. McConn, 631 F.2d 377, 384 (5th Cir. 1980) (holding amplified sound ban in downtown business district was not narrowly tailored because "there is probably no more appropriate place for reasonably amplified free speech than the streets and sidewalks of a downtown business district"); Burbridge v. Sampson, 74 F. Supp. 2d 940, 951 (C.D. Cal. 1999) (Collins, J.) (granting preliminary injunction against rule banning amplified sound on community college campus except in three "preferred areas" because the defendants "failed to rebut Plaintiffs' claim that the 'preferred areas' do not meet the 'ample alternatives for communications' requirement for reasonable content-neutral, time place, and manner regulation"); Lionhart v. Foster, 100 F. Supp. 2d 383 (E.D. La. 1999) (holding that law "regulat[ing] the production of sound in excess of 55 decibels within 10 feet of hospitals or churches during posted services" was "unreasonably overbroad in the context of normal activities on public streets and in public parks").

Of course, even in a traditional public forum, reasonable restrictions on the use of amplified sound are permitted, so long as they are narrowly tailored to serve a significant government interest. But, because "streets, sidewalks, parks and other similar public places are so historically associated with the exercise of First Amendment rights access to them for the purpose of exercising such rights cannot constitutionally be denied broadly and absolutely." Hudgens v. NLRB, 424 u.s. 507, 515 (1976) (quotation marks and citation omitted). The Cit:y's absolute ban on the use of amplified sound twenty-four hours per day on the Boardwalk except in a limited number of specially designated spaces simply sweeps too broadly and does not materially advance the City's proffered interest. Because Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on their claim that the amplified sound ban is facially overbroad (and because, as mentioned earlier, the balance of hardships and the public interest weigh in favor of enjoining regulations that violate the First Amendment), the Court GRANTS Plaintiffs' motion for preliminary injunction with respect to LAMC � 43.15 (F) (5)."

DEAN D. PREGERSON

United States District Judge

"The violinist, William Hassay, asserted that the restriction prevented him from communicating any emotion with his music, and therefore he had stopped playing on the boardwalk. Id. at 512. During a hearing on the plaintiff's motion for a preliminary injunction, two of the Plaintiffs in this case, Mark Chase and Alex Young, testified that they had also been warned and/or cited for violating the restriction. Id. at 513-14. In addition, an expert provided unrebutted testimony that on the boardwalk, a musician needed to play at a level of at least seventy decibels for the music to be intelligible to an audience fifteen feet away. Id. at 524. At seventy decibels, however, the music would also be "easily audible" at a distance of thirty feet and accordingly violate the restriction. Id.

Applying intermediate scrutiny[10] Judge Hollander held that the plaintiff had established a likelihood of success on the merits with respect to his First Amendment claim. Specifically, the restriction was not narrowly tailored to prevent excessive noise and did not leave open ample alternative channels for communication given that, "[i]n effect, the 30-Foot Audibility Restriction [wa]s tantamount to a complete ban on the use of musical instruments and amplified sound on the boardwalk." Id. at 524. Accordingly, this Court entered a preliminary injunction against the enforcement of the restriction as applied to the boardwalk. Id. at 527. Ultimately, the parties jointly requested that the injunction be made permanent. Hassay, 955 F.Supp.2d 505 at ECF No. 43".

New court case decisions about subway performances have been mixed. Performances can happen, but severely restricted including total bans on amplification. See: Young v. New York City Transit Authority, 903 F.2d 146 (2d Cir. 1990); Carew-Reid v. Metropolitan Transportation Auth., 903 F2d 914 (2nd Cir. 1990); Young v. New York City Transit Authority, 903 F.2d 146 (2d Cir. 1990), Wright v. Chief of Transit Police 558 F2d 67 (2d cir. 1977), Loper v. New York City Police Dep't, 999 F.2d 699, 704-05 (2d Cir. 1993). Jews for Jesus v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority 783 F.Supp. 1500 (D. Mass 1991) NOTE: This case was appealed to 1st Circuit Court of Appeals where it was both affirmed and over turned in part. Subway was ruled a First Amendment forum and activity could not be banned, but MBTA could regulate activities for public safety concerns. See: Jews for Jesus v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority 984 F.2d 1319 (1st Cir. 1993) MBTA-Radio Threatens Subway Performances October 2007

Attorney Paul Messing won law suits for saxaphone artist Byrad Lanacaster against the Philadelphia transit system (SEPTA) in 2002 and 2003 with $15,000 and $18,000 damages

Selling of cds, artwork, pins, banners, T-shirts:

The Perry v. Los Angles Police Dept,, 121 F.3d 1368 (9th Cir 1997) ( 9th Circuit site version here ) gave First Amendment protection for street artists, Harry Perry and Robert Newman aka "Jingles," to sell cds, banners, T-shirts and pins on the Venice Beach boardwalk. Additional cases: American Civil :Liberties Union of NV, v. City of Las Vegas, 333 F.3d 1092 (9th Cir. 2003) stated "Sale of merchandise which carries or constitutes a political, religious, philosophical or ideological message falls under the protection of the First Amendment. Gandiya Vaishnava Society v. City of San Francisco, 952 F.2d 1059 (9th Cir. 1990) also protected communicative merchandise sales when done with other First Amendment activity. One World One Family v. City and County of Honolulu 76 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 1996) allowed the ban of T-shirt sales on the sidewalks of Honolulu. Two new Federal Court cases are in process over new restrictions on Venice Beach, CA in 2006-2007.

Court case on protecting visual artists' right to show and sell their artwork-- United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, Bery v. City of NY Decided: October 10, 1996 ( Bery v. New York, 97 F. 3d 684 (2d Cir. 1996 )) cert. denied, 117 S.Ct. 2408 (1997) appeal from Bery, 906 F. Supp 163 (SDNY 1995)) http://csmail.law.pace.edu/lawlib/legal/us-legal/judiciary/second-circuit/test3/95-9089.opn.html See Villanova Sports and Entertainment Law Journal review of the Bery case (5Vill. Sports & Ent. L.J. 103 (1998) http://www.law.villanova.edu/ On-going visual artists and vendors NYC legal battle issues can be found at http://groups.yahoo.com/group/NYCStreetArtists/ or http://www.openair.org/alerts/artist/nyc.html Robert Lederman, President of A.R.T.I.S.T. (Artists' Response To Illegal State Tactics), Ph: 201 896-1686 Email: robert.lederman@worldnet.att.net Site on visual and vendors artists fight in New York City A text version of the Bery v. New York, 97 F. 3d 684 (2d Cir. 1996 ) decision is available on this site by clicking here

Favorite statements from the appellate court in Bery v New York on page 695:The City apparently looks upon visual art as mere "merchandise" lacking in communicative concepts or ideas. Both the court and the City demonstrate an unduly restricted view of the First Amendment and of visual art itself. Such myopic vision not only overlooks case law central to First Amendment jurisprudence but fundamentally misperceives the essence of visual communication and artistic expression. Visual art is as wide ranging in its depiction of ideas, concepts and emotions as any book, treatise, pamphlet or other writing, and is similarly entitled to full First Amendment protection.[3] Indeed, written language is far more constricting because of its many variants--English, Japanese, Arabic, Hebrew, Wolof,[4] Guarani,[5] etc.--among and within each group and because some within each language group are illiterate and cannot comprehend their own written language. The ideas and concepts embodied in visual art have the power to transcend these language limitations and reach beyond a particular language group to both the educated and the illiterate. As the Supreme Court has reminded us, visual images are "a primitive but effective way of communicating ideas. . . a short cut from mind to mind." West Virginia State Board of Education, 319 U.S. at 632.

http://www.rgj.com/news/stories/html/2003/11/21/57307.php?sp1=rgj&sp2=News&sp3=Local+News&sp5=RGJ.com&sp6=news&sp7=local_news&jsmultitag=news.rgj.com/news/local Steven C. White and Ben Klinefelter sued the city of Reno, Nevada in Federal Court (June 2003) over their First Amendment right to sell their work in parks and on streets downtown will receive $47,500 in a settlement. White v. City of Sparks, 341 F.Supp.2d 1129, 1139 (D.Nev.2004)

Three judge 9th Circuit panel ruled against Sparks, Nevada restrictions on displaying and selling art work in public parks and streets. White v. City of Sparks, 05-15582 -- Steven C. WHITE, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. CITY OF SPARKS, Defendant-Appellant. , C.A.9 (Nev.), August 29, 2007 ( 9th Circuit site version here ) White v. City of Sparks Citation: 500 F.3d 953 (9th Cir. 2007) Articles: Artist Has Constitutional Right to Sell Works on Sidewalk — Court by Kenneth Ofgang, Staff Writer, Metropolitan News-Enterprise, Thursday, August 30, 2007 http://www.metnews.com/articles/2007/whit083007.htm No license needed to sell art in parks of Sparks, Nev. By The Associated Press 08.31.07 http://www.firstamendmentcenter.org/news.aspx?id=18987

“In painting, an artist conveys his sense of form, topic, and perspective. A painting may express a clear social position, as with Picasso’s condemnation of the horrors of war in Guernica, or may express the artist’s vision of movement and color, as with ‘the unquestionably shielded painting of Jackson Pollock.’. Any artist’s original painting holds potential to ‘affect public attitudes’. by spurring thoughtful reflection in and discussion among its viewers. So long as it is an artist’s self-expression, a painting will be protected under the First Amendment, because it expresses the artist’s perspective.”

From a court case decided on April 6, 2004 in Christopher Mastrovincinzo (a.k.a. "MASTRO"), and Kevin Santos (a.k.a. "NAC" OR "NAK") v NEW YORK CITY 313 F SUPP 2D 280 (2004) (http://www.nysd.uscourts.gov/rulings/04cv412_040804.pdf) NOTE: This case was reversed 2-1 in the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeal in January 2006 Stated art work such as paintings are protected, but not T-shirts. Mastrovincenzo v. City of New York, 435 F. 3d 78 - Court of Appeals, 2nd Circuit 2006 HERE

"The City's licensing requirement was intended to catch within its net merchants engaged solely in commerce of ready-made goods that clog the sidewalks and compete unfairly with legitimate stores. Applied overbroadly, as Defendants would do, the Ordinance essentially would impose a chilling effect on genuine artists whose true calling is art and not commerce, and whose manifest purpose may be to create expression rather than markets, even if at times some of their work may skirt the line between expressiveness and merchandise. Such an extension of the licensing regime [*293] would force artists to confront an undue dilemma: either to quell their creativity or to risk arrest if they believe their work is sufficiently expressive to fall within the protection of the First Amendment. [HN22] Freedom of expression is designed precisely to bar the government from compelling individuals into that speech-inhibiting choice. See Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844, 871-72 (1997)." Mastrovincenzo v. City of New York, 313 F. Supp. 2d 280, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5804 (S.D.N.Y., 2004)

The 2nd Circut Court of Appeal stated in the lost case:

(1) the sale of clothing painted with graffiti is not necessarily expressive and therefore is not automatically entitled to First Amendment protection;

(2) the sale of plaintiff's clothing nonetheless has a predominantly expressive purpose and therefore merits First Amendment protection;

(3) New York City's licensing requirement is a content-neutral restriction on speech that is narrowly tailored to achieve the objective of reducing urban congestion; and

(4) the Bery injunction's reference to "paintings" does not encompass clothing painted with graffiti.

The decision had a decent opinion and much of the loss was based on narrowing the definition of art in and "ample alternative channels" test.

Mastrovincenzo v. City of New York, 435 F. 3d 78 - Court of Appeals, 2nd Circuit 2006 HEREVenice Beach Boardwalk Vendors - Michael Hunt vs City of Los Angles challenged 2004 law city wrote new law and the selling of soap and incense were not given First Amendment protection. See http://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2011/03/22/09-55750.pdf

Robert Lederman challenged new restrictions by New York City on vendors in parks in 2012 and lost. The appeal to a three judge panel 2nd Circuit Court was also lost in 2013. These were not total bans of vending in parks, but restrictions to vending in designated spots on a First Come, First Serve basis in crowded areas. See: Lederman v. N.Y.C. Dep't of Parks & Recreation, 901 F. Supp. 2d 464, 479 (S.D.N.Y. 2012) HERE; LEDERMAN v. NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION, Docket No. 12–4333–cv. September 25, 2013 http://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-2nd-circuit/1644994.html

Avoid Arrests :

I suggest that all street performers avoid being arrested, if possible. The police officer can avoid the street performing First Amendment issues by charging you with disorderly conduct and /or resisting arrest. It is far better to obtain the name and badge number of the police officer (Do this diplomatically for it puts the individual on guard) and then file a complaint against the city. This way you can determine the issues the court will discuss.

"Because of the sensitive nature of constitutionally protected expression, [the Court has] not required that all those subject to overbroad regulations risk prosecution to test their rights. For free expression; of transcendent value to all society, and not merely to those exercising their rights; might be the loser." Osborne v. Ohio, 495 U.S. 103, 115 n.12 (1990); DOMBROWSKI v. PFISTER, 380 U.S. 479 (1965); (http://laws.findlaw.com/us/380/479.html)

The local chapter of American Civil Liberties Union, Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts or a lawyer from the local arts council will often help street artists for free or reduced fees. This document should help them save time researching the case law on street performing. I have extensive files on this issue including briefs and trial transcripts. This information is offered as a reference tool only. This site is not intended to be legal advice or a substitute for obtaining legal advice from a licensed attorney. Each location has local laws, local judges and not all laws are fair. I strongly suggest you obtain a local licensed attorney to carefully evaluate your individual situation.

Legal and advocacy sites to explore:

- American Civil Liberties Union ACLU http://www.aclu.org

- See the local chapter affiliate page for the office in your state at http://www.aclu.org/affiliates

Two great overview briefs on art censorship:

- The 'Lectric Law Library http://www.lectlaw.com/files/con04.htm

- Artistic Freedom http://www.aclu-mass.org/issuebriefs/artfreedom.html

Many times street artists are arrested and then the officers do not show up for the trial. The case is dismissed, but the harassment and threat of jail often curtails the artists from performing in the future. I do urge you to fight. The exuberant feeling of winning these battles is well worth the effort.

Not all police offices abuse their public safety mandate. Diplomatic, courteous and non -confrontational behavior can often lead to successful resolution of most incidents. Think of each encounter as an opportunity to educate the individual and public on the traditions of street performing.

A police officer who was sent down by a superior can not back down. Arguing with him will be futile. The real battle is with the superior officer. Try to determine if there was a complaint and who is responsible for asking you to leave. Write down names, witnesses, times, locations and as many details as possible. Nine times out of ten there are no complaints and even if there were it is still not enough reason to stop the performance. However, you can only change attitudes by making individuals responsible for their actions. You can not blame the entire police department for one officers' abuse of power, just as you would not want to be accountable for every other street artists' actions.

No musical instruments allowed sign posted in Grant Park in Chicago. These signs were removed after successful negotiations to enact a license permit system along with court challenges in 1983. See American Bar Association Journal, December 1983, Vol 69, page 1816-1817.

A UCLA Department of Urban Planning research book chapter summary on the use of public space can be found on this web site at: Sidewalk Democracy: Municipalities and the Regulation of Public Space

Donations Requested:

IMPORTANT: Please consider sending in a $10 donation for this information. It takes time and money ($500 year) to keep it posted and updated. Make checks payable to Community Arts Advocates, Inc. in US Dollars International Postal Money Orders and send to: Street Arts and Busker Advocates , P.O. Box 300112, Jamaica Plain, MA 02130-0030 USA. Donations can also be made by credit card through the nonprofit Community Arts Advocates see the home page for direct donation link http://www.buskersadvocates.org/ Good luck with your performances and keep me updated and informed of new court cases, legal issues and performance locations.

Stephen H. Baird

Street Arts and Buskers Advocates Legal Citations

- STREET PERFORMING FIRST AMENDMENT PROTECTION FREE SPEECH, FREE EXPRESSION

- STREETS, PARKS, SIDEWALKS AND OTHER PUBLIC PLACES ARE HISTORIC FIRST AMENDMENT FORUMS

- AIRPORTS, BUS STATIONS, SUBWAY PLATFORMS AND SIMILAR PUBLIC SPACES DETERMINED TO BE FIRST AMENDMENT FORUMS

- CAMPUSES AS FIRST AMENDMENT TERRITORY

- MALLS AND OTHER PRIVATE, SEMI-PRIVATE SPACES AS FIRST AMENDMENT TERRITORY

- CONTRIBUTIONS LEGALLY PROTECTED

- RIGHT TO HEAR & TO CONTRIBUTE

- USING THE FEAR OF FRAUD AND LIABILITY AS GUISE FOR CENSORSHIP RIGHT TO HEAR & TO CONTRIBUTE

- REGULATION TIME, PLACE AND MANNER

FREE SPEECH, FREE EXPRESSION

Street performing, like other art forms, is protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments both historically and legally. Singing of broadsides was one of the earliest and most prevalent forms of the press. Plays, dances, and singing have always been associated with expression of religious sentiment. The US Supreme Court has stated: "Each medium of expression, of course, must be assessed for First Amendment purposes by standards suited to it. "the basic principles of freedom of speech and the press, like the First Amendment's command, do not vary. Those principles, as they have frequently been enunciated by this Court make freedom of expression the rule." Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad,, 420 US 546 , 557-558, (l974) http://laws.findlaw.com/us/420/546.html

quoting Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 US 503 (l952).

Music is protected under the First Amendment as a form of expression and communication.

Music is one of the oldest forms of human expression. From Plato's discourse in the Republic to the totalitarian state in our own times, rulers have known its capacity to appeal to the intellect and to the emotions, and have censored musical compositions to serve the needs of the state. See 2 Dialogues of Plato, Republic, bk. 3, pp. 231, 245-248 (B. Jowett transl., 4th ed. 1953) ("Our poets must sing in another and a nobler strain"); Musical Freedom and Why Dictators Fear It, N.Y. Times, Aug. 23, 1981, section 2, p. 1, col. 5; Soviet Schizophrenia toward Stravinsky, N.Y. Times, June 26, 1982, section 1, p. 25, col. 2; Symphonic Voice from China Is Heard Again, N.Y. Times, Oct. 11, 1987, section 2, p. 27, col. 1. The Constitution prohibits any like attempts in our own legal order. Music, as a form of expression and communication, is protected under the First Amendment. In the case before us the performances apparently consisted of remarks by speakers, as well as rock music, but the case has been presented as one in which the constitutional challenge is to the city's regulation of the musical aspects of the concert; and, based on the principle we have stated, the city's guideline must meet the demands of the First Amendment. Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781, 790, 109 S.Ct. 2746, 2753, 105 L.Ed.2d 661 (1989) http://laws.findlaw.com/us/491/781.html

Excerpted from: N.Y. Law Journal Monday 8/17/98. Judge Refuses to Enforce Permit Rule for Artists

A New York City Parks Department rule requiring a $25 monthly license to sell artwork, books or other written matter in the parks or on sidewalks adjacent to the parks is not enforceable, a Manhattan Criminal Court judge has ruled in dismissing misdemeanor charges against three artists who were arrested for unlicensed vending.

". the City demonstrate an unduly restricted view of the First Amendment and of visual art itself. Such myopic vision not only overlooks case law central to First Amendment jurisprudence but fundamentally misperceives the essence of visual communication and artistic expression. Visual art is as wide ranging in its depiction of ideas, concepts and emotions as any book, treatise, pamphlet or other writing, and is similarly entitled to full First Amendment protection.

Bery v. New York, 97 F. 3d 684 (2d Cir. 1996)UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Nos. 1620, 1621, 1782 August Term 1995(Argued: April 26, 1996 Decided: October 10, 1996) Docket Nos. 95-9089 (L), 95-9131, 96-7137 Bery v. New York, 97 F. 3d 684 (2d Cir. 1996)

From a court case decided on April 6, 2004 in Christopher Mastrovincinzo (a.k.a. "MASTRO"), and Kevin Santos (a.k.a. "NAC" OR "NAK") v NEW YORK CITY 313 F SUPP 2D 280 (2004) NOTE: This case was reversed 2-1 in the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeal in January 2006 details will be posted shortly. Stated art work such as paintings are protected, but not T-shirts. 435 F.3d 78; 2006 U.S. App. LEXIS 157

"The City's licensing requirement was intended to catch within its net merchants engaged solely in commerce of ready-made goods that clog the sidewalks and compete unfairly with legitimate stores. Applied overbroadly, as Defendants would do, the Ordinance essentially would impose a chilling effect on genuine artists whose true calling is art and not commerce, and whose manifest purpose may be to create expression rather than markets, even if at times some of their work may skirt the line between expressiveness and merchandise. Such an extension of the licensing regime [*293] would force artists to confront an undue dilemma: either to quell their creativity or to risk arrest if they believe their work is sufficiently expressive to fall within the protection of the First Amendment. [HN22] Freedom of expression is designed precisely to bar the government from compelling individuals into that speech-inhibiting choice. See Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844, 871-72 (1997)." Mastrovincenzo v. City of New York, 313 F. Supp. 2d 280, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5804 (S.D.N.Y., 2004)

See the following cases: Tinker v Des Moines Independent School District, 393 US 503 (l969) black arm band; Spense v Washington 4l8 US 405 (l974) peace symbol taped on flag; Cohn v California, 403 US l5 (l97l) words "Fuck the Draft" sewn onto a jacket; Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v Wilson, 343 US 495 (l952) film "Miracle"; Jankins v Georgia, 4l8 US l53 (l973) film "Carnal Knowledge"; Doran v Salem Inn, Inc. 422 US 922 (l975) nude dancing; Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v Conrad 420 US 546 (l975) Musical Theatre "Hair;" Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781, 790, 109 S.Ct. 2746, 2753, 105 L.Ed.2d 661 (1989) rock music; White v. City of Sparks Citation: 500 F.3d 953 (9th Cir. 2007) selling art work in pubic park; Lionhart v. Foster 100 F.Supp.2d 383 (E.D.La.,1999) street performing with amplification; Davenport v Alexandria, 683 F2d 853 (1983), 710 F2d 148 (1983), 748 F2d 208 (1984) street performing; Friedrich v. Chicago 619 F. Supp. 1129 (D.C. Ill 1985) street performing; Turley vs NYC 988 F.Supp, 667 & 675 (1997) street performing with amplification; and Goldstein v Town of Nantucket 477 F. Supp. 606 (l979) street performing. In the last the US District Court of Massachusetts stated:

"Troubadour's public performance of Nantucket's traditional folk music was clearly within the scope of protected First Amendment expression." Goldstein v Town of Nantucket, 477 F. Supp. 606, 608 (l979)

STREETS, PARKS, SIDEWALKS AND OTHER PUBLIC PLACES ARE

HISTORIC FIRST AMENDMENT FORUMS

The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that sidewalks, streets and parks are important First Amendment forums. See: Hague v. CIO 307 US 496; Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 394 US 147 (1968); Amal. Food Emp. U. Loc. 590 v. Logan Val. Plaza, 391 US 308 (1968); Coates v. City of Cincinnati, 402 US 611 (1971); and Grayned v. City of Rockford, 408 US 104 (1972), Perry Education Assn. v. Perry Local Educators' Assn., 460 U.S. 37 (1983), Frisby v. Schultz, 487 U.S. 474, 480 (1988), "Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they have immemorially been held in trust for use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions. Such use of the streets and public places has, from ancient times, been a part of the privileges, immunities, rights, and liberties of citizens." Hague v. CIO., 307 US 496, 515-516 (opinion of Mr. Justice Roberts, joined by Mr. Justice Black) Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 394 US 147 , 152 (1968) http://laws.findlaw.com/us/394/147.html

". we have repeatedly referred to public streets as the archetype of a traditional public forum." "Our prior holdings make clear that a public street does not lose its status as a traditional public forum simply because it runs through a residential neighborhood." "No particularized inquiry into the precise nature of a specific street is necessary; all public streets are held in the public trust and are properly considered traditional public fora."

Street performances have been ascertained as an appropriate First Amendment activity on sidewalks, streets and parks in the following cases: Celli v. City of St. Augustine: 214 F.Supp.2d 1255 (M.D. Fla. 2000) (http://www.ncac.org/art-law/op-cel.cfm); Davenport v Alexandria, 683 F2d 853 (1983), 710 F2d 148 (1983), 748 F2d 208 (1984) street performing; Friedrich v. Chicago 619 F. Supp. 1129 (D.C. Ill 1985) street performing; and Goldstein v Town of Nantucket 477 F. Supp. 606 (l979) street performing. In the last the US District Court of Massachusetts stated:

"streets, sidewalks, parks, and other similar public places are . historically associated with the exercise of First Amendment rights. " Amal. Food Emp. U. Loc. 590 v. Logan Val. Plaza, 391 US 308 (1968). Goldstein v Town of Nantucket, 477 F. Supp. 606, 608 (l979)

A reason given for prohibiting street performers is the availability of other public areas. The Following US Supreme Court statement has been frequently quoted in numerous lower court decisions:

"One is not to have the exercise of his liberty of expression in appropriate places abridged on the plea that it may be exercised in some other place." Schneider v State, 308 US l47 , l63 (l939). http://laws.findlaw.com/us/308/147.html

AIRPORTS, BUS STATIONS, SUBWAY PLATFORMS AND SIMILAR PUBLIC SPACES

DETERMINED TO BE FIRST AMENDMENT FORUMS

There are many court cases dealing directly with First Amendment activities on subway platforms, bus stations, and airports. The Hare Krishnas have been involved in many of these cases. The following is a partial list, for there are volumes of cases: ISKCON v Collins 452 F. Supp. 1007 (1977) (Houston airport); ISKCON v Rochford 425 F. Supp. 734 (1974) (Chicago airport); ISKCON v Griffin 437 F. Supp. 666 (1977) (Pittsburg airport); ISKCON v New York Port Authority 425 F. Supp. 681 (1974) (NY bus station); Wolin v Port Authority of New York 392 F. 2d 83 (1968), (NY bus station); Public Utilities Commission v Pollack 343 US 451 (bus station); Lehman v Shaker Heights 418 US 298 (1974) (busses); Wright v Chief of Transit Police 558 F. 2d 67 (1977), (selling magazines in a New York subway station); AIRPORT COMM'RS v. JEWS FOR JESUS, INC., 482 U.S. 569 (1987), (airport); INTERNATIONAL SOC. FOR KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS v. LEE, 505 U.S. 672 (1992), (airport); etc.

There is an account about Charles Bandy and William Brown, two New York street performers, who were arrested, tried, and acquitted for performing on the streets and subways of New York, which appeared in the New Yorker on October 6, 1966 (This story was also featured several time in the New York Times). The NY ACLU represented the artists.

More recently, in the Criminal Court of the City of New York subway platforms were determined to be a First Amendment forum:

"For First Amendment purposes, no distinction can be wrought between a subway platform and the public street. People v. St. Clair, 56 Misc. 2d 326 (Criminal Ct. N.Y. Co. 1968). The State of New York has adopted the policy of deeming any rapid transit facility constructed by and at the expense of a city containing more than one million people a part of the public streets of that city. Rapid Transit L. Sec. 31 (e)." People of the State of New York v. Roger ManningDocket #5N038025V (Sept. 10, 1987)

The Chicago street performing ordinance in question before the Federal Court in Friedrich v. Chicago 619 F. Supp. 1129 (D.C. Ill 1985); 110 FRD 340 (N.D. Ill 1986); regulated performances on the streets, sidewalks, parks, and transit platforms. The First Amendment rights of the street performers to perform on the streets, sidewalks, parks, and transit platforms were upheld. On appeal, the time, place and manner restrictions were vacated.

New cases include New York News v. MTA, 753 F. Supp. 133 (S.D.N.Y. 1990); Young v. New York City Transit Authority, 903 F.2d 146 (2nd Cir. 1990) bans begging and appeal denied by US Supreme Court; Carew-Reid v. Metropolitan Transportation Auth., 903 F2d 914 (2nd Cir. 1990); bans amplification.

This case ruled a leafleting ban on subway platforms unconstitutional and even cited the subway musicians as an example of a First Amendment activity that caused no safety issues.

"The factual circumstances that transform plaintiffs' activity into a threat to public safety exist only in specified stations at specified times; most stations during most hours of operation are not so crowded. Moreover, the range of transit activities occurring within defendant's stations rebuts its contention that leafleting threatens public safety. Indeed, the arguments defendant advances apply with similar force to permitted activities, including the newspaper hawkers and the musicians." Jews for Jesus v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority 783 F.Supp. 1500 (D. Mass 1991) NOTE: This was cased was appealed to 1st Circuit Court of Appeals where it was both affirmed and over turned in part. It was ruled a First Amendment forum and activity could not be banned, but MBTA could regulate activities for public safety concerns. See: 984 F2d 1319 (1st Cir. 1993)

The Supreme Court in a deeply divided decision in INTERNATIONAL SOC. FOR KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS v. LEE, 505 U.S. 672 (1992) declared the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey airport terminal interior sections not a public forum. The airport had stores, post offices, banks, restaurants and sidewalks which are open to general public. The distinction between the open public areas and secured areas was not considered. Case followed logic of private mall court cases plus ignored exaggerated public safety issues as a guise for censorship.

"One of the places left in our mobile society that is suitable for discourse is a metropolitan airport. It is of particular importance to recognize that such spaces are public forums because, in these days, an airport is one of the few government-owned spaces where many persons have extensive contact with other members of the public. Given that private spaces of similar character are not subject to the dictates of the First Amendment, see Hudgens v. NLRB, 424 U.S. 507 (1976), it is critical that we preserve these areas for protected speech. In my view, our public forum doctrine must recognize this reality, and allow the creation of public forums that do not fit within the narrow tradition of streets, sidewalks, and parks. We have allowed flexibility in our doctrine to meet changing technologies in other areas of constitutional interpretation, see, e.g., Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967), and I believe we must do the same with the First Amendment."

CAMPUSES AS FIRST AMENDMENT TERRITORYINTERNATIONAL SOC. FOR KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS v. LEE, 505 U.S. 672 (1992) JUSTICE KENNEDY, with whom JUSTICE BLACKMUN, JUSTICE STEVENS, and JUSTICE SOUTER

If there be any doubt, the scope of the First Amendment covers private and state campus communities. The US Supreme Court has stated: "At the outset we note that state colleges and universities are not enclaves immune from the sweep of the First Amendment. the precedents of this Court leave no room for the view that, because of the acknowledged need for order, First Amendment protections should apply with less force on college campuses than in the community at large. Quite to the contrary, "[T]he vigilant protection of constitutional freedoms is nowhere more vital than in the community of American schools." Shelton v Tucker 364 US 479, 487 (l960)." Healy v James, 408 US l69 , l80 (l97l) http://laws.findlaw.com/us/408/169.html

The majority of the college and university communities, by reason of the Twenty-sixth Amendment (l8 years of age eligible to vote), are composed of free voting citizens. The US Supreme Court has stated:

"Many people in the United States live in company-owned towns. These people, just as residents of municipalities, are free citizens of their State and country. Just as all citizens they must make decisions which affect the welfare of community and nation. To act as good citizens they must be informed. In order to enable them to be properly informed their information must be uncensored. There is no more reason for depriving these people of the liberties guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments than there is for curtailing these freedoms with respect to any other citizens."

"When we balance the Constitutional rights of owners of property against those of the people to enjoy freedom of press and religion, as we must here, we remain mindful of the fact that the latter occupy a preferred position."

Marsh v Alabama, 326 US 50l , 508-509 (l945) http://laws.findlaw.com/us/326/501.htmlSee also the Court cases Brooks v Auburn University 296 F. Supp. l88 (MD Ala. l969); Wright, The Constitution on the Campus 22 Vand. L. Rev. l027 (l969), University of So. Miss. MCLU v University of So. Miss. 452 F. Ed. 564 (l97l); Snyder v Board of Trustees of University of Illinois, 286 F. Supp. 927, 932 (ND Ill. l968); New Left Education Project v Board of Regents of the University of Texas 326 F. Supp. 158 (1970) (Public University) and State of New Jersey v Chris Schmid N.J. 423 A.2d 615 (1980) (Supreme Court affirmed decision) (Private University - Princeton University).

Clearly various forms of the First Amendment guarantees&emdash;selling of newspapers, attendance of religious services, and free expression&emdash;are important parts of the college and university communities. See Keegan v Univ. of Del. Del. Supr. 349 A 2d l4 (l975), Dickey v Alabama State Board of Ed., 273 F. Supp. 6l3 (l967); Troy State Univ. v Dickey 402 F. 2d 5l5 (5th cir. l968). Lee v Board of Regents of State Colleges 306 F. Supp. l097 (WD Wis. l969); Close v Lederle 303 F. Supp. ll09 (D. Mass. l969); New Left Education Project v Board of Regents of the University of Texas 326 F. Supp. 158 (1970) (Public University) and State of New Jersey v Chris Schmid N.J. 423 A.2d 615 (1980) (Supreme Court affirmed decision) (Private University - Princeton University).

Many forms of First Amendment expression are allowed and encouraged to penetrate the campus communities from the outside, including areas for viewing commercial television, rebroadcasting commercial radio stations over intercom systems, spaces for selling newspapers and magazines, and space for religious activity.

Space is even allocated for strictly commercial activities (cigarette and soft drink vending machines, etc.) and entertainment activities (pinball and electronic games, pool tables, etc.) Surely space is available for individual First Amendment expression.

"While Auburn may establish neutral priorities and require adequate coordination, this Court is clear to the conclusion that it can not altogether close its available facilities to outside speakers." Brooks v Auburn University, 296 F. Supp. l88, l98, CMD Ala. (l969).

"The overriding issue as to use of school facilities for non-academic purposes is not raised. Thus, while there may be no duty to open the doors of the school houses for uses other than academic&emdash;and I have some doubt even as to this proposition&emdash;once they are opened they must be opened under conditions consistent with constitutional principle. Buckley v Meng 230 NYS 2d 924, 933 (l962)."

Brooks v Auburn University, 296 F. Supp. l88, l93, (MD Ala. l969).

Another reason given for prohibiting street performers is the availability of other public areas off campus. The US Supreme Court has stated:

"One is not to have the exercise of his liberty of expression in appropriate places abridged on the plea that it may be exercised in some other place." Schneider v State, 308 US l47 , l63 (l939). http://laws.findlaw.com/us/308/147.html

Specifically, the US District Court WD Virginia has stated:

"In a case litigating college students' rights to hear speakers prohibited from speaking on campus by a speaker-ban law, it has been noted: "[I]t is no objection to plaintiff's standing here to assert that they could have heard (the prohibited speaker) at some off-campus location. " quoting Snyder v Board of Trustees of University of Illinois, 286 F. Supp. 927, 932 (N.D. Ill. l968)." ACLU of Virginia v Radford College, 3l5 F. Supp. 893, 898 (l970).

MALLS AND OTHER PRIVATE, SEMI-PRIVATE SPACES AS FIRST AMENDMENT TERRITORYMalls account for 50% to 70% of all merchant sales in 21 of the largest cities in 1973 (See Pruneyard 153 Cal. Reporter, page 860). Since 1973, not only has the number of suburban malls increased, there has been extensive growth in the number of downtown urban malls, which can only enlarge those percentages (See Time, August 24, 1981). The public street of America are becoming the private street of merchants. The acquisitions of streets coupled with the financial control of the various elements of the mass media means access to public thought is increasingly being funneled through fewer and fewer people with an increasing price tag.

All this has not gone unnoticed in the courts. On the public streets the issue is clear-cut. Judge Rya Zobel stated,

"The requirement of merchants' approval is irreconcilable with freedom of expression. It is unqualified censorship and it is just what the First Amendment forbids." Goldstein V. Nantucket 477 F. Supp. 606, 609 (1979).The Supreme Court has not been clear on the issues of malls (private property) and freedom of speech. At first the courts decided in favor of free speech in Marsh v. Alabama (Company owned town, 1945) and in Amalgamated Food Employees Union v. Logan Valley Plaza (Mall, 1967). The courts then started to rule in favor of private property in Lloyd Corp. v. Tanner (Mall, 1972) and Hudgens v. National Labor Relations Board (Mall, 1975). The latest twist in this issue occurred when the court ruled that malls in California could be considered public property under the California Constitution in Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robbins (1980). (This last case could make the audition systems at Pier 39, The Cannery and Ghiradelli Square in San Francisco unconstitutional.)

The only consistent voice was Justice Marshall. The following is excerpted from his dissenting opinion in Lloyd Corp. v. Tanner:

For many persons who do not have easy access to television, radio, the major newspapers, and other forms of mass media, the only way they can express themselves to a broad range of citizens on issues of general public concern is to picket, or to handbill or to utilize other free or relatively inexpensive means of communication. The only hope that these people have to be able to communicate effectively is to be permitted to speak in those areas in which most of their fellow citizens can be found. One such area is the business district of a city or town or its functional equivalent.

It would not be surprising in the future to see cities rely more and more on private businesses to perform functions once performed by governmental agencies. The advantages of reduced expenses and increased tax base cannot be overstated. As governments rely on private enterprise, public property decreases in favor of privately owned property. It becomes harder and harder for citizens to find means to communicate with other citizens. Only the wealthy may find effective communication possible unless we adhere to Marsh v. Alabama mad continue to hold that "(t)he more an owner, for his advantage, opens up his private property for use by the public in general, the more do his rights become circumscribed by statutory and constitutional rights of those who use it."

Rouse Company malls have been sued in civil court numerous times for First Amendment violations. The case in Boston was decided in Federal Court on August 27, 1990 Citizens to End Animal Suffering v Faneuil Hall Marketplace, Inc., 745 F. Supp. 65 (1990) and determined that animal rights activists had a right to picket and protest at Faneuil Hall Marketplace They were arrested for passing out leaflets to restaurant patrons to not eat veal. Judge Tauro stated Faneuil Hall Marketplace must be considered within its historical context and cannot be considered private property.

The 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decided on October 9, 2002, that the Mormon church cannot restrict speech on the sidewalks running through its plaza in Salt Lake City, Utah. The plaza was once a part of the Main Street and was sold to the church. However, to ensure pedestrian access, the city retained easement rights. The First Unitarian Church in Salt Lake City with support from the ACLU successfully sued the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints restrictions on demonstrations and protests on the plaza.

"Because sidewalks are a traditional public forum the city should protect free-speech rights there." "The city cannot create a 'First Amendment-free zone.'" First Unitarian Church of Salt Lake v. Salt Lake City, 308 F3d 1114 (10th Cir. 2002) http://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-10th-circuit/1160780.html

http://www.acluutah.org/legal-work/resolved-cases/item/191-first-unitarian-church-v-salt-lake-city-corporationCentral deciding factors in the last two cases were the "retained public easement rights," plus both were historical public spaces and former public streets. Similar case: American Civil Liberties Union, NV v. City of Las Vegas 333 F3d 1092 (9th Cir. 2003)

CONTRIBUTIONS LEGALLY PROTECTED

Leaving an instrument case open for voluntary compensation and receiving money for records and tapes are often the central issues. Derogatory remarks like "begging" and "panhandling" are usually directed at street artists. The US Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected attempts to ban First Amendment activity because it included solicatation or financial gain. See: Schneider v State, 308 US l47, (1939) MURDOCK v. PENNSYLVANIA 319 US 105,. (1943) ; Bigelow v Virginia, 421 US 809 (1974) ; Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, 425 US 748, (1975) ; Schaumburg v Citizens for Better Environment, 444 U.S. 620, (1979) Heffron v. International Soc. for Krishna Consciousness, Inc., 452 U.S. 640 (1981); RILEY v. NATIONAL FEDERATION OF BLIND, 487 U.S. 781 (1988)

The US Supreme Court has stated:

"But the mere fact that the religious literature is 'sold' by itinerant preachers rather than 'donated' does not transform evangelism into a commercial enterprise. If it did, then the passing of the collection plate in church would make the church service a commercial project. The constitutional rights of those spreading their religious beliefs through the spoken and printed word are not to be gauged by standards governing retailers or wholesalers of books. The right to use the press for expressing one's views is not to be measured by the protection afforded commercial handbills. It should be remembered that the pamphlets of Thomas Paine were not distributed free of charge."

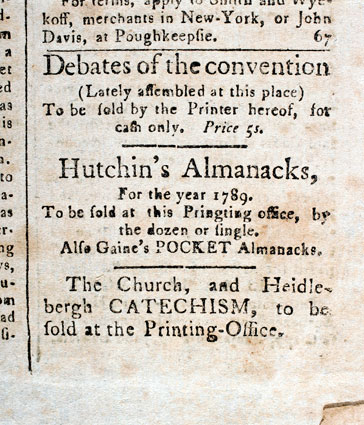

(Click on image to see larger version)

Common Sense was printed and Sold by R. Bell, Third Street Philadelphia in 1776. Thomas Paine donated some of the publication sales profits to support the Continental Army. President George Washington was so grateful that he asked the first Congress to purchase and give a New Rochelle, New York estate to Thomas Paine. ( http://www.thomaspaine.org/ ).

"The fact that the particular advertisement in appellant's newspaper had commercial aspects or reflected the advertiser's commercial interest did not negate all First Amendment guarantees. The State was not free of constitutional restraint because the advertisement involved sales or "solicitations." Murdock v Pennsylvania 3l9 US l05, ll0-lll (l943), or because appellant was paid for printing it, New York Times Co. v Sullivan, 376 US at 266; Smith v California, 36l US l47, l50 (l959) or because appellant's motive or the motive of the advertiser may have involved financial gain, Thomas v Collins 323 US 5l6, 53l (l945). The existence of commercial activity in itself is not justification for narrowing the protection of expression secured by the First Amendment, Ginzburg v United States 383 US 463, 474 (l966)."

"Speech likewise is protected even though it is carried in a form that is 'sold' for profit. Smith v California 36l US l47 l50 (l959) (books); Joseph Burstyn Inc. v Wilson 343 US 495, 50l (l952) (motion pictures)"

"Murdock v Pennsylvania 3l9 US at lll (religious literature) and even though it may involve a solicitation to purchase or otherwise pay or contribute money."

"Last term in Bigelow v Virginia, 42l US 809 (l974) the notion of unprotected 'commercial speech' all but passed from the scene."

Specifically, the US District Court of Massachusetts has stated:

"The fact that plaintiff troubadour accepted contributions of passersby during his public performances would not dilute his protection under the First Amendment." Goldstein v Town of Nantucket, 477 F. Supp. 606, 609 (l979)

Las Vegas police arrest street performers for soliciting contributions and tips lose 9th Circuit Court of Appeals Decision May 24, 2017 HERE. KTNV TV story Here Las Vegas Sun story: Here

"Additionally, the solicitation of tips is “entitled to the same constitutional protections as traditional speech.” ACLU of Nev. v. City of Las Vegas, 466 F.3d 784, 792 (9th Cir. 2006). Municipalities accordingly may not ban either “passive” solicitation of tips for street performance (e.g., putting a hat out or saying “thank you”), or “active” solicitation (e.g., encouraging a tip orally or by tipping a hat). SANTOPIETRO 14 V. HOWELL See Berger, 569 F.3d at 1052. If only “active” solicitation is banned, “an officer seeking to enforce [that] ban ‘must necessarily examine the content of the message that is conveyed.’” Id. (quoting Forsyth Cty. v. Nationalist Movement, 505 U.S. 123, 134 (1992)). As a content-based regulation of speech in a public forum, such a ban is subject to strict scrutiny, a standard not met by a distinction between active and passive solicitation of voluntary tips. Id. at 1052–53. Metro’s 2010 MOU appears to incorporate that holding, by recognizing that “non-coercive solicitation of tips[] is not a per se violation” of the County Code’s business licensing provisions."

ACLU of Nev. v. City of Las Vegas, 466 F.3d 784 (2006)

"It is beyond dispute that solicitation is a form of expression entitled to the same constitutional protections as traditional speech. See Vill. of Schaumburg v. Citizens for a Better Env't, 444 U.S. 620, 628-32, 100 S.Ct. 826, 63 L.Ed.2d 73 (1980); see also ISKCON, 505 U.S. at 677, 112 S.Ct. 2701; Gaudiya Vaishnava Soc'y v. City of San Francisco, 952 F.2d 1059, 1063-64 (9th Cir.1990). "Regulation of a solicitation must be undertaken with due regard for the reality that solicitation is characteristically intertwined with informative and perhaps persuasive speech . and for the reality that without solicitation the flow of such information and advocacy would likely cease." Riley v. Nat'l Fed'n of the Blind of N.C., Inc., 487 U.S. 781, 796, 108 S.Ct. 2667, 101 L.Ed.2d 669 (1988) (internal quotation marks omitted) (alteration in original). The City bears the burden of justifying its restriction. Bay Area Peace Navy v. United States, 914 F.2d 1224, 1227 (9th Cir.1990)."

A. Economic Viability

Clearly the street performing concept and the individual's expressed ideas have to be economically viable in order to survive in our present economic system. The US Supreme Court has stated:

"Soliciting financial support is undoubtedly subject to reasonable regulation but the latter must be undertaken with due regard for the reality that solicitation is characteristically intertwined with informative and perhaps persuasive speech seeking support for particular causes or for particular views on economic, political or social issues, and for the reality that without solicitation the flow of such information and advocacy would likely cease." Schaumburg v Citizens for Better Environment, 444 U.S. 620 (1979). http://laws.findlaw.com/us/444/620.html

B. Economic Censorship

A crucial aspect in only allowing street performers under prepaid contracts is the use of authority and money to censor what people hear.

"The very purpose of the First Amendment is to foreclose public authority from assuming a guardianship of the public mind through regulating the press, speech, and religions. In this field every person must be his own watchman for truth, because the forefathers did not trust any government to separate the true from the false for us." Thomas v Collins, 323 US 5l6 , 545 (l944), http://laws.findlaw.com/us/323/516.html

J. Jackson concurring

"State supported university was not required to allocate funds from student fees or from public monies to pay invited speakers. university could not for no constitutionally acceptable reason, withhold funds for one speaker as a censorship device."

Brooks v Auburn University, 296 F. Supp. l88, l89(MD Ala. l969)

C. Campus Solicitation

A number of court challenges of both public and private campus solicitation regulations have occurred. See: New Left Education Project v Board of Regents of the University of Texas 326 F. Supp. 158 (1970) (Public University) and State of New Jersey v Chris Schmid N.J. 423 A.2d 615 (1980) (Private University - Princeton University).

"University rules prohibiting sale of publications and other solicitations on campus except as authorized by the administration, without any standard governing the issuance of such authorization, were invalid as licensing regulations affecting First Amendment rights without adequate guidelines." New Left Ed. Proj. v Board of Regents of the U. of Texas, 326 F. Supp. 158 (1970)

"Private University's regulations, which were devoid of reasonable standards designed to protect legitimate interest of the university as institution of higher education and individual exercise of expressional freedom, could not constitutionally be invoked to prohibit otherwise noninjurious and reasonable exercise of such freedom, and thus the university violated state constitutional rights of defendant by evicting him and securing his arrest for distributing political literature upon its campus." (This case included distribution and sale of materials by the Labor Party members.)

State of New Jersey v Chris Schmid N.J., 423 A.2d 615 (1980)

Anti begging and solicitations statues have been unconstitutional in Massachusetts since the ruling in Benefit v. City of Cambridge, 679 N.E. 2d 184 (Mass 1997).

Peaceful begging constitutes communicative activity protected by the First Amendment" 424 Mass at 923. Benefit v. City of Cambridge, 679 N.E. 2d 184 (Mass 1997).

Note -- see article reviewing case: Benefit and Begging: By Frank J. Bailey and John C. La Liberte Statute Prohibiting Peaceful Pleas for Charity in Public Places Violates First Amendment - Benefit v. City of Cambridge at http://www.sherin.com/publication_detail.asp?p=14

Final note: Even the U.S. Constitution was printed sold with a published and fixed price during the ratification process. Below are copies of the first printing of the U.S. Constitution by The Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser on September 19, 1787, with a (Price Four-Pence.) at the top left corner (Library of Congress); Federalist Papers, printed and sold by J. and A. McLean (Library of Congress); and Poughkeepsie Country Journal details of "Debates of the convention" for sale for 5s.

RIGHT TO HEAR & TO CONTRIBUTE

An equally alarming aspect of the street performing bans is the violation of the community's First Amendment right to listen. "There is a First Amendment right to peacefully assemble to listen to speakers of one's choice, which may not be impaired by state legislation any more than the right of speaker may be impaired." Snyder v Board of Trustees of University of Illinois, 286 F. Supp. 927, 928, (ND Ill. l968).

"'The Supreme Court has recognized that hearers and readers have rights under the First Amendment. Lamont v Postmaster General 38l US 30l 85 S. Ct. l493 l4 L. Ed. 2d 398 (l965). What is implicit in the majority opinion is made explicit in the concurring opinion of Justices Brennan and Goldberg: [T]he addressees assert First Amendment claims in their own right: they contend that the Government is powerless to interfere with the delivery of the material because the First Amendment necessarily protects the right to receive it."

Brooks v Auburn University, 296 F. Supp. l88, l92 (MD Ala. l969).

The instrument case is open for the expression of gratitude. Financial remuneration is only one element of such expression; poems, sketches, notes, letters, ceramics and art work is often donated.

"(T)he protection of the Bill of Rights goes beyond the specific guarantees to protect from congressional abridgment those equally fundamental personal rights necessary to make the express guarantees fully meaningful. (citing cases) I think the right to receive publications is such a fundamental right. The dissemination of ideas can accomplish nothing if otherwise willing addressees are not free to receive and consider them. It would be a barren marketplace of ideas that had only sellers and no buyers." Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 US 301 , 308 (1965) http://laws.findlaw.com/us/381/301.html (Brennan, J., concurring)

USING THE FEAR OF FRAUD AND LIABILITY AS GUISE FOR CENSORSHIP

Protecting the public from fraud and harassment is often the excuse for prohibiting street art and music. The US Supreme Court has stated: "Conceding that fraudulent appeals may be made in the name of charity and religion we hold a municipality cannot, for this reason, require all who wish to disseminate ideas to present them first to police authorities for their consideration and approval. Frauds may be denounced as offenses and punished by law." Schneider v State, 308 US l47 , l64 (l939). http://laws.findlaw.com/us/308/147.html

"State regulation of labor unions, whether aimed at fraud or other abuses, must not infringe constitutional rights of free speech and free assembly."

"The Village's legitimate interest in preventing fraud can be better served by measures less intrusive than a direct prohibition on solicitation. Fraudulent misrepresentations can be prohibited and the penal laws used to punish such conduct directly."

". the ordinance does not pass First Amendment scrutiny is that it is not tailored to the Village's stated interests. Even if the interest in preventing fraud could adequately support the ordinance insofar as it applies to commercial transactions and the solicitation of funds, that interest provides no support for its application to petitioners, to political campaigns, or to enlisting support for unpopular causes. The Village, however, argues that the ordinance is nonetheless valid because it serves the two additional interests of protecting the privacy of the resident and the prevention of crime.

With respect to the former, it seems clear that �107 of the ordinance, which provides for the posting of "No Solicitation" signs and which is not challenged in this case, coupled with the resident's unquestioned right to refuse to engage in conversation with unwelcome visitors, provides ample protection for the unwilling listener. Schaumburg, 444 U. S., at 639 ("[T]he provision permitting homeowners to bar solicitors from their property by posting [no solicitation] signs . suggest[s] the availability of less intrusive and more effective measures to protect privacy"). The annoyance caused by an uninvited knock on the front door is the same whether or not the visitor is armed with a permit."

The relationship between the street artists and audience is intrinsically honest. Payment usually occurs after a performance and each individual determines the means, the amount, and the way in which compensation is given."A free society prefers to punish the few who abuse rights of speech after they break the law than to throttle them and all others beforehand." Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v Conrad, 420 US 546 , 559 (l974). http://laws.findlaw.com/us/420/546.html

"While university can prohibit disruptive or fraudulent solicitation on campus, it must do so in manner that strikes at the very evil to be prevented."

New Left Ed. Proj. v Board of Regents U. of Tex. Sys., 326 F. Supp. 158 (1970)

The newest issue used to curtail the First Amendment rights of street artists and public is liability. Cities and towns are requiring insurance for people to demonstrate and perform. The Eleventh Circuit United States Court of Appeals stated in a decision on April 15, 2004:

"We readily conclude that the indemnification provision in the Augusta-Richmond Ordinance fails to provide adequate standards. It requires an indemnification agreement "in a form satisfactory to the attorney for Augusta, Georgia," � 3-4-11(a)(3), and gives no guidance regarding what should be considered "satisfactory." Thus, the requirement is standardless and leaves acceptance or rejection of indemnification agreements "to the whim of the administrator." Thomas, 534 U.S. at 324, 122 S.Ct. at 781 (citing Forsyth County, 505 U.S. at 133, 112 S.Ct. at 2403)." Martha BURK, Chair, National Council of Women's Organizations, National Council of Women's Organizations, et al., v. AUGUSTA-RICHMOND COUNTY, Consolidated Government, Augusta-Richmond County Commission, et al. No. 03-11756. April 15, 2004 (365 F.3d 1247; 2004 U.S. App. LEXIS 7261; 17 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. C 425)

A similar case was decided in Boston in September, 2004.

"US District Court Judge Douglas P. Woodlock found that it was discriminatory for the General Services Administration to require Catherine Van Arnam to sign an indemnity clause when applying for a license to hold a rally outside the John. F. Kennedy Building. The judge wrote that the regulation essentially forces those seeking permits to seek liability insurance to cover damages, and therefore discriminates against protesters who can't affor such insurance." Boston Globe, September 2, 2004.

See: CATHERINE VAN ARNAM, et al., Plaintiffs, v. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION, et al., Defendants. CIVIL ACTION NO. 00-10879-DPW (332 F. Supp. 2d 376; 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 17213)

REGULATION TIME, PLACE AND MANNER

Clearly cities and campuses can regulate time, place, and manner of speech, but regulations must be in clear and narrow terms and be the least restrictive so as not to punish protected speech. See Schneider v State 308 US l47, l60, l62; Brooks v Auburn University 296 F. Supp. l88, l94 (MD Ala. l969); MCLU at So. Miss. University v So. Miss. University 452 F. 2d 564 (l97l); Krishna v Bowen 456 F. Supp. 437, 443 (SD Ind. l978); ACLU of Virginia v Radford College 3l5 F. Supp. 893 (l970); State v Schmid N.J. 423 A.2d 615 (1980); New Left Ed. Proj. v Board of Regents U. of Tex. Sys. 326 F. Supp. 158 (1970) and Thomas v Collins 323 US 5l6, 530 (l945) etc. "Speech may be suppressed only when it presents a clear and present danger that substantive evil will result. Courts must ask whether gravity of evil, discounted by its improbability justifies such invasion of free speech as necessary to avoid danger." Snyder v Board of Trustees of Univ. of Ill., 286 F. Supp. 927 (l968).

". free expression may be prohibited only if they materially and substantially interfere with requirements of appropriate discipline in operation of school.' Tinker v Des Moines Independent Community School District 393 US 503 (l969)."

MCLU of So. Miss. Univ. v So. Miss. Univ., 452 F 2d 564, 5l6 (l97l).

Public safety is an appropriate consideration for regulation of First Amendment rights. However, one must remain cognizant that the First Amendment must have receivers and listeners. See the court cases: Stanley v. Georgia 394 US 557 (1968); Pell v. Procunier 417 US 817 (1973); Giswuld v. State of Conn, 381 US 479 (1964); and Lamont v. Postmaster General 381 US 301 (1965). In the last:

"(T)he protection of the Bill of Rights goes beyond the specific guarantees to protect from congressional abridgment those equally fundamental personal rights necessary to make the express guarantees fully meaningful. (citing cases) I think the right to receive publications is such a fundamental right. The dissemination of ideas can accomplish nothing if otherwise willing addressees are not free to receive and consider them. It would be a barren marketplace of ideas that had only sellers and no buyers." Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 US 301 , 308 (1965) http://laws.findlaw.com/us/381/301.html

(Brennan, J., concurring)

There necessarily must be some kind of crowd and even if there is a safety problem there are many regulation alternatives which allows First Amendment activity to continue. The US Eastern District Court of Louisiana found the First Amendment considerations outweighed any congestion problem and stated:

"Ordinance prohibiting solicitation in one section of city imposed unconstitutional burden on religious group which solicited donations in such section where funds solicited paid for literature and propagation of the religion in that section in which members of the group felt they might be more successful in reaching prospective converts, and burden was not justified even if section was focal point of interest for visitors and residents and because of its unique design its avenues of transportation were outmoded." ISKCON, Inc. v. City of New Orleans, 347 F. Supp. 945 (1972)

The US Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit affirmed the decision of the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia protecting Lee Davenport's First Amendment right to perform bagpipes on the sidewalks of Alexandria, Virginia:

"there has been shown no safety interest substantial enough to outweigh the plaintiff's First Amendment interests." Davenport, No. 81-709-A (E.D. Va. Nov. 16, 1983). Davenport v. City of Alexandria, VA, 748 F.2d 208 (1984)

The courts have often stated that it is unconstitutional to ban a broad range of activity to protect the public from disruptive behavior. See: Hammond v. S.C. State College, 272 F. Supp. 947, 950 (D.S.C. 1967); Grayned v. City of Rockford, 408 US 104 (1972); Carroll v. President and Comr's of Princess Anne, 393 US 175 (1975); and Coates v. City of Cincinnati, 402 US 611, 614 (1971).

"The city is free to prevent people from blocking sidewalks, obstructing traffic,littering streets, committing assaults, or engaging in countless other forms of anti-social conduct. It can do so through the enactment and enforcement of ordinances directed with reasonable specificity toward the conduct to be prohibited." Coates v. City of Cincinnati, 402 US 611, 614 (1971). http://laws.findlaw.com/us/402/611.html

". requiring a permit as a prior condition on the exercise of the right to speak imposes an objective burden on some speech of citizens holding religious or patriotic views. As our World War II-era cases dramatically demonstrate, there are a significant number of persons whose religious scruples will prevent them from applying for such a license. There are no doubt other patriotic citizens, who have such firm convictions about their constitutional right to engage in uninhibited debate in the context of door-to-door advocacy, that they would prefer silence to speech licensed by a petty official."

"Third, there is a significant amount of spontaneous speech that is effectively banned by the ordinance. A person who made a decision on a holiday or a weekend to take an active part in a political campaign could not begin to pass out handbills until after he or she obtained the required permit. Even a spontaneous decision to go across the street and urge a neighbor to vote against the mayor could not lawfully be implemented without first obtaining the mayor's permission. In this respect, the regulation is analogous to the circulation licensing tax the Court invalidated in Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233 (1936). In Grosjean, while discussing the history of the Free Press Clause of the First Amendment, the Court stated that " `[t]he evils to be prevented were not the censorship of the press merely, but any action of the government by means of which it might prevent such free and general discussion of public matters as seems absolutely essential to prepare the people for an intelligent exercise of their rights as citizens.' " Id., at 249-250 (quoting 2 T. Cooley, Constitutional Limitations 886 (8th ed. 1927)); see also Lovell v. City of Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938)."

NOTE: Rediscovering the Center City (Doubleday 1988) by William H. Whyte The author, William H. Whyte, was an expert architect witness in favor of street performances in the Davenport v. Alexandria, Virginia and the Friedrich v. Chicago, Illinois federal court cases. He provided important testimony to rebut the exaggerated and bogus public safety issues often presented by city officials to suppress and ban street performances. Details of this issue can be found in the third chapter. William H. Whyte also wrote an earlier book titled The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces which documented street performances and pedestrian behavior. The detailed research with film and photographic documentation plus pedestrian surveys show people will "self regulate" crowds to minimize danger to personal safety. See: Project for Public Spaces, 700 Broadway, New York, NY 10003-9536 Fred Kent, President, Phone: 212 620-5660, Fax: 212 620-3821 Email: pps@pps.org Web site: http://www.pps.org/

- Safety & Security in Public Space, Project for Public Spaces http://www.pps.org/info/placemakingtools/issuepapers/safety_security

- Campaign to Preserve the Commons: Keeping the 'Public' in Public Space, Project for Public Spaces http://www.pps.org/info/placemakingtools/issuepapers/commercialize

- A UCLA Department of Urban Planning research book chapter summary on the use of public space can be found on this web site at: Sidewalk Democracy: Municipalities and the Regulation of Public Space � Stephen H. Baird 2008 Disclaimer: The information here is offered as a reference tool only. No information or materials posted here are intended to constitute legal advice. This site is not intended to be legal advice or a substitute for obtaining legal advice from a licensed attorney. Further, this site does not constitute an attorney-client relationship. Local counsel should always be consulted. No guarantee or warranty, express or implied, is given with regard to the current accuracy of any information provided and Community Arts Advocates, Inc. and Stephen H. Baird shall not be liable for any damages or liability whatsoever arising from the information provided herein. It is strongly recommend consulting a licensed attorney to carefully evaluate your individual situation.

Street Arts and Buskers Advocates

- Street Arts Advocates Email List

- Code of Ethics

- Legal Issues

- Legal Court Citationsarticle by Stephen Baird

- Goldstein v. Town of Nantucket, 477 F. Supp., 606, (1979)

- Davenport v Alexandria, VA 683 F2d 853 (1983), 710 F2d 148 (1983), 748 F2d 208 (1984)

- Friedrich v Chicago 619 F. Supp., 1129. (D.C. Ill 1985)

- Carew-Reid v. Metropolitan Transportation Auth., 903 F2d 914 (2nd Cir. 1990)(Subway)

- Jews for Jesus v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (1991)(Subway)

- Bery v. New York, 97 F. 3d 684 (2d Cir. 1996)

- Turley v. NYC 988 F.Supp, 667 & 675 (1997). See US 2nd Cir Appeal 98-7114 (1999)

- Perry v. LAPD, US 9th Cir Appeals 96-55545 (1997)

- Horton v. St. Augustine, Florida US 11th Cir Appeal No. 00-16220 (2001)

- Christopher Mastrovincinzo (a.k.a. "MASTRO"), and Kevin Santos (a.k.a. "NAC" OR "NAK") v NEW YORK CITY 313 F SUPP 2D 280 (2004)

- Overview with articles and photographs

- Police Rule 75

- Federal Law Suit to protect rights of street artists in Boston

- Complaint Motion

- Preliminary Injunction Motion

- Response From City of Boston

- Reply and Second Memorandum

- Federal Court Hearing December 17, 2004

- City Repeals Police Rules and Regulations determined Unconstitutional in Federal Court on December 23, 2004

- Issues and timeline

- Media articles

- Petition

- Overview with articles and photographs

- December 2003 MBTA Restrictions Battle

- Wesleyan University Olin Fellowship Thesis by Maggie Starr

- MBTA-Radio Threatens Subway Performances October 2007

- Overview with articles and photographs

- Cambridge, MA Ordinance

- Overview with articles and photographs

- Historical statement by Stephen Baird

- Davenport v Alexandria, VA 683 F2d 853 (1983), 710 F2d 148 (1983), 748 F2d 208 (1984)

- Overview with articles and photographs

- Overview with articles and photographs

- Urban Studies Statement by Dr. Allan Schnaiberg, Professor of Sociology and Urban Affairs at Northwestern University

- Friedrich v Chicago 619 F. Supp., 1129. (D.C. Ill 1985)

- Summary

- Letter

- Ordinance

- Petition

- New Orleans Code

- Mayor LaGuadia bans New York City street entertainers 1935

- South Street Seaport

- Horton v. St. Augustine, Florida US 11th Cir Appeal No. 00-16220 (2001)

- Salt Lake City, Utah Ordinance

- Santa Cruz Street Performance Voluntary Guidelines

- Citizens to End Animal Suffering v Faneuil Hall Marketplace, Inc., 745 F. Supp. 65 (1990)

- Cambridge, MA

- Worcester, MA

- Chicago, IL

- Hartford, CT

- East Lansing, MI

- St. Louis, MO

- Toledo, OH

- Santa Monica, CA

- Sidewalk Democracy: Municipalities and the Regulation of Public Space

- Introduction

- North America

- South America

- Europe

- Asia , Australia, New Zealand , Africa

- Avenues of Self Expressionarticle by Stephen Baird

- Ben Franklin on the Streets of Boston in 1718

- Busking in Colonial Williamsburg in 1738

- Rope Walking from Church Steeple in 1757

- Patrick Henry and Sam Adams on the Revolutionary Streets

- Nathaniel Hawthorne "All vagrants are interesting"

- Boston Street Music 1869